Biomonitoring: Tracking the health risks of incineration

In 2023/24, over 50 per cent of the UK’s municipal waste was incinerated. Although emissions are tightly monitored, there is an emerging discipline that seeks to check there are no adverse impacts in the local environment. Beth Jones investigates.

Waste incineration is the most pervasive substitute for landfilling, and has offered a solution to one of the UK’s overarching waste management challenges. In 2023/24, incinerators dealt with 12.6 million tonnes of waste, representing over half (50.2 per cent) of all local authority-managed waste.

Waste incineration is the most pervasive substitute for landfilling, and has offered a solution to one of the UK’s overarching waste management challenges. In 2023/24, incinerators dealt with 12.6 million tonnes of waste, representing over half (50.2 per cent) of all local authority-managed waste.

The number of facilities across England has risen in recent years, increasing from 38 to 52 in five years. This trend is not limited to just England; Scotland has also experienced a rise in incinerated waste, with 2023 levels nearly three times those recorded in 2011.

However, as the sector expands, so does public concern - particularly around the environmental and health implications of resulting emissions. While carbon capture and storage (CCUS) technologies are being trialled to mitigate carbon dioxide output, the broader spectrum of pollutants emitted by incinerators remains contentious.

The state of biomonitoring research in the UK

One approach to assessing pollution exposure is biomonitoring - the analysis of biological materials such as blood, breast milk, animal tissue, or vegetation to track cumulative pollutant uptake.

Unlike traditional air quality monitoring, which captures pollutants at specific moments in time, biomonitoring provides a more holistic picture of long-term exposure, spanning weeks, months, or even years.

Despite growing interest, no government-funded or university-led projects in the UK have systematically assessed the long-term impact of incinerators on nearby populations using biomonitoring. According to the UK Environment Agency (EA), there are no current plans to carry out any sampling for persistent organic pollutants (POPs) next to incinerators.

The longer-term focus of biomonitoring could provide a useful basis for studying POPs, which are toxic chemical substances that resist degradation in the environment, accumulate in the food chain, and pose risks to human health.

Discussing the possibility of these projects in the UK, United Kingdom Without Incineration Network (UKWIN) said: “UKWIN would welcome biomonitoring studies at incineration sites across the UK. We are aware that biomonitoring studies carried out by colleagues in Europe have revealed unacceptable levels of pollution in the vicinity of municipal waste incinerators.”

Can biomonitoring be successful?

In contrast to the UK’s limited efforts, several European countries have adopted a proactive stance. Zero Waste Europe’s (ZWE) ‘The True Toxic Toll’ initiative undertook biomonitoring studies across Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Slovakia, and Spain.

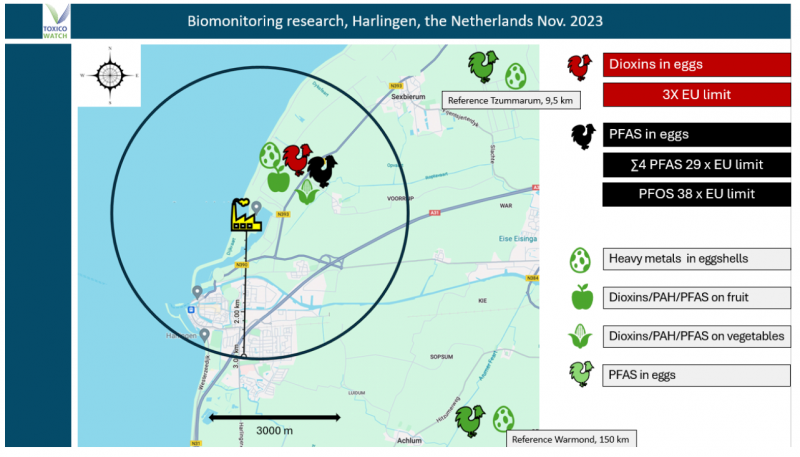

Using spatial zoning models (sampling within 2 km, 3 km, and 5 km radii from incinerators), researchers collected and analysed samples from environments most affected by pollutant dispersion, such as areas downwind of emission stacks. The image below demonstrates the results of a research project in the Netherlands, comparing samples from within a 3 km radius of the REC waste incinerator to reference locations between 8 km and 150 km away.

The samples were then analysed using strict traceability protocols to provide a picture of the environmental impact of incinerator emissions. Key findings included:

- Elevated levels of dioxins and furans - groups of chemicals produces as unintentional by-products of waste incineration - in backyard chicken eggs near incinerators, sometimes exceeding EU safety limits for food consumption

- Increased amounts of PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) - a group of synthetic chemicals once widely used in electrical equipment, heat transfer fluids, and other industrial applications - that can cause a range of health issues and have been banned or restricted in the UK

- Higher concentrations of POPs in vegetation and soil close to incineration sites, suggesting the deposition of pollutants from airborne emissions

- Evidence of bioaccumulation: pollutants building up in living organisms over time

- Heavy metals including lead, mercury, and arsenic detected in areas close to homes, parks and schools

These findings were not limited to spaces next to incinerators. One study in Paris saw soil and moss samples taken from Ivry-sur-Seine show dioxin levels above EU safety thresholds in parks located 2.5 km from the incinerator.

Describing these concerns, Janek Vahk, Zero Pollution Manager at ZWE, commented: “Although modern incinerators are designed to operate within legally permissible emissions limits, this research demonstrates that such thresholds are not sufficient to prevent environmental and biological contamination. In several cases, pollutant levels in nearby chicken eggs exceeded EU food safety limits for dioxins and PCBs, despite the facilities being in formal compliance.”

“Biomonitoring provides tangible evidence of bioaccumulation that emission stack measurements alone cannot, revealing a persistent gap between regulatory performance and actual environmental health outcomes.”

The European Suppliers of Waste-to-Energy Technology (ESWET) - which represents the incineration industry - has pushed back against studies like 'The True Toxic Toll', arguing that they fail to establish direct causation between incinerators and detected pollutants, as well as not accounting for historical pollution.

According to ESWET, modern WtE plants in Europe are highly regulated, with strict limits on emissions. They argue that existing air quality monitoring is sufficient and that biomonitoring studies often lack the necessary controls to isolate incinerators as the primary source of contamination.

Limitations of biomonitoring

While biomonitoring offers a tool to assess exposure to pollutants, it is not without its challenges.

One of the primary challenges is establishing causality. Though pollutants may be detected in biological samples, determining whether they originated from incineration is difficult, especially in urban or industrial regions with multiple pollution sources.

Moreover, biomonitoring studies have yielded variable outcomes. While some indicate elevated toxin levels near older incinerators, others, particularly those focused on modern facilities, show negligible differences. These inconsistencies may result from differing methodologies, sample sizes, or environmental factors.

Practical barriers also hinder adoption. Biomonitoring is resource-intensive, requiring coordinated sampling efforts, long-term funding, and specialised analytical capabilities. The need for repeated testing over extended periods to track trends compounds these logistical and financial challenges.

Are incinerators bad for human health?

Originally designed to handle organic waste, incinerators are now increasingly used to burn plastics, as food waste is more often redirected to anaerobic digestion or composting.

An investigation from the BBC has suggested that burning household waste is now the most polluting form of power generation in the UK, with a carbon intensity comparable to that of coal. With the UK reducing its coal usage, this has left incinerators as the ‘dirtiest way the UK produces power’.

Incinerators release a variety of emissions, including:

Incinerators release a variety of emissions, including:

- Carbon dioxide (CO2)

- Nitrous oxide (N2O)

- Oxides of nitrogen (NOx)

- Ammonia (NH3)

- Total Carbon (C)

A 2023 report from the UKWIN linked these emissions to a variety of potential health risks, particularly in communities located near incinerator sites. Pollutants such as fine particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide are of significant concern due to the absence of any known safe exposure level.

Explaining the main health and environmental concerns of incinerators, Shlomo Dowen, UKWIN's National Coordinator, commented: “At a time when improving the quality of the air we breathe is a priority, incinerators take us in the wrong direction by worsening air quality. Incinerators contribute to worsening air quality through the direct emissions of a range of toxic substances and gasses.

Adding to these concerns, a recent investigation reported by the Guardian found elevated levels of certain chemicals in the breast milk of women living near incinerators, raising concerns about bioaccumulation. Although the study called for further investigation, the findings reinforce apprehensions about long-term exposure.

Emissions limits on incinerators

However, not all studies point to direct harm. Research conducted by Imperial College London, which evaluated over one million births across England, Scotland, and Wales, found no strong evidence linking incinerator proximity to increased risks of premature birth, low birth weight, or stillbirth.

The EA and the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) maintain that modern incinerators, regulated under stringent emissions standards, pose minimal risk to public health.

A Spokesperson from the EA commented: “Energy-from-waste facilities must meet strict emission limits for a wide range of pollutants.

“We also consult the UK Health Security Agency on every permit application for a new EfW plant and will only grant a permit if we are satisfied that the plant will not cause significant environmental pollution or harm to human health.”

Currently, all plants must comply with the requirements set out in the Industrial Emissions Directive, including the use of best available techniques to minimise emissions. There are limits for emissions of pollutants with each plan subjected to regular audits and inspections by the EA.

According to UKWIN, “the Environment Agency does a better job regulating incinerators than local councils (who are responsible for regulating Small Waste Incineration Plants). However, the situation is still far from one where the incineration industry can genuinely be seen as ‘well regulated’.”

Future directions: improving research and policy

Whilst the practice of biomonitoring may have its limitations, environment campaigners argue that a more comprehensive approach to monitoring is needed. ZWE suggests that biomonitoring is one way to ensure that regulatory bodies measure actual human and ecological exposure rather than relying solely on emissions modelling and stack measurements.

"Zero Waste Europe is calling on EU institutions and national governments to take urgent and decisive action to address the public health risks posed by waste incineration," the organisation stated. "Specifically, we advocate for the introduction of mandatory, real-time monitoring of POP emissions from all Waste-to-Energy facilities, with particular attention to periods of non-standard operations (OTNOC), which remain poorly regulated yet are frequent sources of emission spikes."