Southeast Asian communities flooded with plastic waste since China ban

Communities in Southeast Asia have been flooded with plastic waste diverted from China following the introduction of the Chinese Government’s waste ban at the start of 2018, according to a new report.

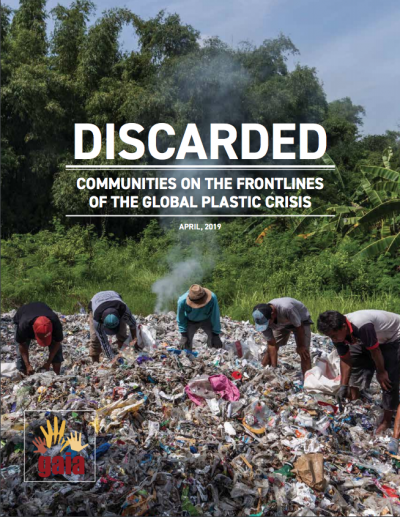

The report by the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA) and Greenpeace, entitled ‘Discarded: Communities on the frontlines of the global plastic crisis’, brings the impact of China’s waste ban on communities in Southeast Asia into stark relief.

At the start of 2018, the Chinese Government imposed bans on a range of solid wastes, including unsorted mixed papers and post-consumer plastics, and strict contamination limits of 0.5 per cent for all other waste materials from 1 March 2018 – limits so strict as to constitute an effective ban.

At the start of 2018, the Chinese Government imposed bans on a range of solid wastes, including unsorted mixed papers and post-consumer plastics, and strict contamination limits of 0.5 per cent for all other waste materials from 1 March 2018 – limits so strict as to constitute an effective ban.

While the ban raised questions of quality for exporters, with exporters and industry figures calling for vast improvements in quality so as not to completely close off the export route to China, many exporters have redirected their waste exports to other markets, particularly those in Southeast Asia such as Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia.

Following the ban, UK plastic exports to China fell by 97 per cent, while exports to Malaysia tripled and exports to Thailand increased by fifty times in the first four months of 2018. This led some countries to impose their own import restrictions in a bid to stem the tide of plastic imports threatening to overwhelm their waste management infrastructure. Malaysia has since banned plastic waste imports altogether while Thailand intends to do the same from 2021.

Catastrophic for communities

While the diversion of waste exports from China to alternative markets was convenient for exporters, the consequences have been catastrophic for communities in countries such as Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia – the focus of the GAIA report – with the flood of plastic waste in particular leading to contaminated water supplies, crop death, respiratory illness from exposure to burning plastic and the rise of organised crime.

The report continues: ‘Plastic waste – and the environmental and health problems it causes – was diverted to other shores, stressing infrastructure and amplifying the problems of plastic pollution in lower-income countries awash in the trash of wealthy nations.’

The nations bracing themselves against the onslaught of plastic waste have struggled to enforce new bans due to lack of personnel and resources, leading to the illegal import of waste and its inappropriate disposal upon arrival.

In order to stem the flow of plastic waste, the report calls for wealthy nations to take responsibility for their own waste and drastically reduce the production and consumption of single-use plastics ‘as it becomes abundantly clear that the world cannot recycle its way out of plastic pollution’.

This is particularly problematic as plastic manufacturing is not set to slow down any time soon, with global production predicted to increase by 40 per cent in the next 10 years.

‘Passing the burden’

Commenting on the report, Beau Baconguis, regional plastics coordinator at GAIA Asia Pacific, said: “As wealthy nations dump their low-grade plastic trash onto country after country in the Global South, the least the international community can do is safeguard a country’s right to know exactly what is being sent to their shores.

“However, ultimately, exporting countries need to deal with their plastic pollution problem at home instead of passing the burden onto other communities.”

Kate Lin, a senior campaigner with Greenpeace East Asia, added: “Once one country regulates plastic waste imports, it floods into the next un-regulated destination. When that country regulates, the exports move to the next one.

“It’s a predatory system, but it’s also increasingly inefficient. Each new iteration shows more and more plastic going off grid – where we can’t see what’s done with it – and that’s unacceptable.”

Zoë Lenkiewicz, Head of Programmes and Engagement at environmental charity WasteAid, which helps marginalised communities to deal with their waste sustainably, commented: "This report highlights the depressing irony of plastic waste being exported from wealthy countries to poor parts of the world that don't even have systems in place for their own waste. It raises questions about the UK's claimed recycled achievements and demonstrates that we cannot wash our hands of waste materials once they leave our shores. There really is no away."

What is happening to our recycling?

Over the past few years, the practice of exporting recyclable waste, especially plastic waste, has come under increasing scrutiny. In July 2018, the UK’s National Audit Office (NAO) released a report highlighting the risk that waste exported for recycling may not actually be recycled. For example, in the UK, when packaging waste is exported, a Packaging Export Recovery Note (PERN) is issued once the waste is sent abroad, denoting that the waste has been recycled. However, the PERN does not cover what happens to the waste once it arrives at its destination.

The NAO report concluded that the UK’s plastic packaging recycling rate – currently reported as 39 per cent – ‘could be overstated’ due to flawed monitoring and oversight in the system. A significant proportion of the UK’s growth in packaging recycling rates are down to the growth in exports, with the total amount of packaging waste exported increasing sixfold since 2002.

Such claims have led to demands that the UK and other wealthy nations deal with the waste that they generate domestically, with UK MPs recently calling for a total ban on plastic waste exports to developing countries and demanding that ‘the government should not pass the buck to the Global South on plastic’. The government has previously pledged to help developing countries to deal with plastic pollution, with a whole chapter of the Resources and Waste Strategy dedicated to the topic, while Prime Minister Theresa May has pledged £61.4 million to tackle marine plastic pollution through a global alliance of Commonwealth states.

Stimulate secondary materials markets and reduce single-use plastics

With the waste export system facing increasing criticism, there is a drive to stimulate domestic markets for recyclable materials, which would in turn encourage investment in domestic reprocessing facilities that would reshore the UK’s waste and prevent the need for export.

In late 2017, the government released its Industrial Strategy, which placed emphasis on strengthening the UK’s domestic market for secondary materials in order to move towards a more circular economy. At an international level, the EU announced in early 2018 that its Plastics Strategy would also focus on the establishment of secondary markets for recycled plastics within Europe. It was also announced in the UK Treasury’s Autumn Statement that a tax on the manufacture and import of plastic packaging containing less than 30 per cent recycled plastic will be introduced from 2022 to drive domestic demand for recycled plastic.

Governments around the world are also legislating to reduce single-use plastics, with the European Parliament voting to ban certain single-use plastics as part of the EU’s Plastics Strategy in March 2019. The UK has banned the manufacture of cosmetic and personal care products containing microbeads and the government is also considering a ban on plastic straws, drinks stirrers and cotton buds in England.

You can read the full GAIA report – ‘Discarded: Communities on the frontlines of the global plastic crisis’ – on the organisation’s website.