Recycling 101: Targeting high quality in Taiwan

Taiwan’s recycling rate is one of the highest in the world and the country secures an array of high quality material from households. Charles Newman visited an MRF to see what Taiwan is doing right

As one of the manufacturing powerhouses of the world, Taiwan has a voracious appetite for raw material. In turn, this has created a demand for recyclables and a system to efficiently collect and sort them.

Today, the country recycles over 55 per cent of its municipal waste and, according to the benchmarking report from environmental consultants Eunomia, ‘Recycling – Who Really Leads the World?’, it had the second best household recycling of OECD countries in 2016. To get to this point has required aligning the packaging producers, recycling companies, public and government over the past 20 years.

In 1997, the Taiwan Environment Protection Administration (EPA) established a public-owned and public-run Recycling Fund Management Board, the mechanism for managing the system of extended producer responsibility that manufacturers and importers pay into. Backed by legislation, the Waste Disposal Act, as well as this money, EPA has been able to develop a comprehensive recycling infrastructure for the public.

Sung Hsin-Chen, the Deputy Executive Security of the Recycling Fund Management Board, explains that the public are required to play their part: “The law means that we can fine people who do not separate [their recycling] well, but typically the government [operatives] will just ask people to do it again. Some local governments will check the garbage to see if there are any recyclables and will send it back.”

What helps is that Taiwanese householders bring their recyclables and waste to collection vehicles when they come round. Loudly playing a garish melody (much akin to that of an ice-cream van), two trucks appear together at designated stopping points in a neighbourhood. One a flat-bed lorry to take a vast array of dry recyclables and sometimes food waste, the other a classic refuse compactor vehicle for the residual waste. When these stop, operatives supervise the loading of sacks of recyclables and waste, providing an opportunity to reject anything unsuitable.

I witnessed this happening on the streets of Taipei, where most packaging waste is presented in clear sacks, with glass and other materials handled separately. These trucks, I was informed, will pass through a neighbourhood several times a day, though less frequently in more rural areas (where there are also recycling centres for residents to bring material).

In the capital and adjoining administrative district, New Taipei City, households have to purchase blue bags for their residual waste; the translucent bags for recycling are free. This pay-as-you-throw approach, not replicated anywhere else in Taiwan, is a key reason why the recycling rate for Taipei is almost 70 per cent.

Hsin-Chen highlights the role schools have played enabling the public to adapt to sorting recyclables. “The teachers will ask [students] to separate their garbage and usually the kids will go home and tell their parents that they have to do it.”

Although the system only requires classification into three categories – food waste, dry recyclables and general waste – most local authorities ask residents to separate materials into many more collection streams. To see the result of this, I visited a materials recycling facility (MRF) in the adjoining administrative district of Taoyuan City, 50 kilometres to the west of Taipei. Like most of the recycling infrastructure in Taiwan, it’s privately owned, working to contract for the local government.

The Taiwanese MRF

Located next to a motorway, the first thing that’s apparent is the facility is not as smelly as I would expect; MRFs in the UK have a pronounced odour. Predictably, there’s a weighbridge at the entrance, over which a large fleet of modest trucks with cages on the back arrive and depart, managed by traffic lights in the adjacent monitoring station.

First stop for the trucks after weigh-in is a drop off for flammables, such as aerosols, batteries, lighters, etc. Then there’s an opportunity to unload electrical items. I note there are neat arrangements of monitors and computer keyboards. A man sits nearby stripping wires and parts out of the equipment. These are just the first two areas of the site. In total, I’m informed, this 41,000-tonne capacity MRF manages 11 streams covering approximately 70 materials.

Evidence of this is apparent as the truck moves to its next drop off, the glass sorting shed. Glass is collected separately to other materials in a durable large white sack that hangs off the back of the vehicle, to be tipped into an arrival bay. A wheeled loader then shovels the mixed glass onto a conveyor belt on a raised level for sorting, where operatives pick out glass according to its colour and throw it down a shoot to the specific colour bay.

This split level approach is replicated in the main 100-metre-long sorting shed, where the dry recyclables (mostly presented in clear plastic sacks) are subsequently dropped off. Here, there is a little bit more automation, with optical sorting at the front end to pick out packaging plastics (PET, LDPE, etc.) for further sorting elsewhere, as well as paper and light card. The rest of the materials then go along the conveyor belt with people to pick them for their selected bays.

Technically, the collection of dry recyclables in Taiwan can be classified as co-mingling. Yet, inspecting the bays of different sorted materials provides evidence that not compacting recyclables during collection makes them easier to sort and dramatically reduces contamination. Here in the Taoyuan MRF, I even noted individual bays for polystyrene and hard plastics, materials that would never be collected with dry recyclables in the UK. Elsewhere on the site, there is a plethora of bays for other materials the collectors are prepared to take onboard the trucks, including pushchairs, tyres, textiles and fluorescent tubes.

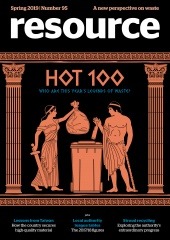

This article was taken from Issue 95

This article was taken from Issue 95The Taiwanese approach clearly has benefits. Although there’s no kerbside collection from right outside their home (arguably an Anglo-American phenomenon), citizens have the opportunity to take a wide array of unwanted items to the collection trucks when they stop in their neighbourhood.

Somewhat remarkably, the MRF pays the Taoyuan Government NT$1,175 per tonne (about £30) to collect and sort the material, plus an additional five per cent of any income earned per tonne for sales above NT$1,175. This in itself is likely to create an effective driver for operatives to avoid contamination.

Despite this, there are inevitably rejects. According to Yu-Wei Hong, the MRF’s matriarch owner, the facility has a reject rate of 15 per cent. Yet the material in the reject bay looks eminently recyclable – the inference was that the MRF did not have to pay for this material and there is a real focus on quality.

On the way back to Taipei from the Taoyuan MRF, Hsin-Chen informs me that since China set strict contaminant restrictions on imported recyclables, the EPA has noted an increase in significantly contaminated material imported from countries such as the UK and United States. She said that they were considering action, as they had been watching the levels of waste from reprocessors.

A few weeks after visiting Taiwan I received a notice that it was taking action. Although not specifying a relevant contamination level for sorted paper and plastic, the amendment to the Waste Disposal Act follows China in stating that material imported should not be general mixed paper or plastic.

It’s evident that in a country that has a great demand for recyclable materials to reprocess, there’s a recognition of what makes them fit for purpose. This goes some way to explaining why its household recycling service targets high-quality material.