Pay-as-you-throw in Seoul: Turning down the volume

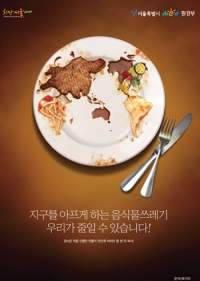

Faced with rampant growth in waste generation, the Korean government introduced a pay-as-you-throw system in 1995. Edward Perchard investigates how Seoul is putting its foot down on waste.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Seoul’s pay-as-you-throw system, with citizens and businesses charged depending on the waste they actually generate. In 1995, the Korean government had run out of options: waste from the industrial and commercial powerhouse was pouring in, while space was running out.

Extraordinary economic growth in the second half of the 21st century –‘the Miracle on the Han River’ – saw South Korean gross domestic product (GDP) per capita grow from $92 (£59) in 1961 to $12,333 (£8,019) in 1995. This boom brought wealth and, along with it, waste, fuelled by swathes of people moving to the cities. Ninety per cent of the population now lives in cities, 20 per cent in Seoul alone, and the new-found purchasing power led to unprecedented consumption. By 1981, each Korean was creating an average of 1.77 kilogrammes (kg) of waste per day, compared to 0.7kg in Germany and 0.8kg in Japan. And there was simply nowhere for it to go.

In the early ’90s, landfill took more than 90 per cent of waste created in South Korea, a country the size of Iceland, most of which is mountain. In often-cramped London, the population density is around 14,200 people per square mile, while Seoul packs 43,000 souls into each square mile. And the cost of waste collection to each household was traditionally based on size, offering no incentive to cut down: the bigger the house, the higher the cost. In 1994, waste disposal nationwide cost 962 billion won (£543 million), but the flat collection fee returned just 142.8 billion won (£80 million) to government coffers.

And so, in 1995, in addition to making incineration the treatment option of choice, the South Korean government enforced a volume-based fee (VBF) waste system for households, businesses and office buildings. The system uses designated and district- specific biodegradable bags for residual waste that can be bought from local shops in sizes ranging from three to 100 litres. Prices vary, but a pack of 10 20-litre bags goes for around 4,000 won (£2.29) while a single 50-litre bag will cost about 1,050 won (60p). Recycling, however, has remained free – at least in most districts – encouraging residents to maximise their separated recycling.

The immediate response to the system was mixed. Professor Hong Jong Ho, from the Graduate School of Environmental Studies at Seoul National University, tells a story of one of his students just after the system’s introduction: “He was living in a house with other college students, all living in separate rooms. He purchased the bag and he put his waste in there. But the next morning he returned and found it all spread out on the ground. The bag he had bought was gone – someone had stolen it.”

He continues: “There were lots of complaints at first. But the government did lots of advertisement with support from NGOs and experts. People knew that our land size is very limited and they did not like the idea of having landfill near their house, even if it’s sanitary.” And so, within a year, total waste generation had fallen from 58,118 tonnes per day to 47,774 – a reduction of 17.8 per cent. It hasn’t dropped since (generation was lowest in 1998 – 44,583 tonnes a day), but it hasn’t gone up significantly either (until an upward creep in the last few years), while recycling has consistently risen to a current rate of around 49 per cent after a first-year jump from 15 to 24 per cent. The four incinerators, meanwhile, experienced an operation rate 40 per cent lower than expected after generation dropped so significantly, and, as of 2012, the system brings in revenue to cover approximately 30 per cent of waste disposal costs (compared to the 14 per cent in 1994).

At first, there was a sharp increase in litter disposed of in ‘illegal bags’, in alleyways and on hillsides, and of waste being illegally incinerated, but video surveillance systems were introduced and local environment groups and citizens’ movements began monitoring the problem. Violators were subjected to fines, with a maximum of around £500, and, from 2000, anyone reporting the unlawful activity received as much as 80 per cent of the fine.

The fight to reduce waste goes on, however. Expansion continues – both in the sense of GDP per capita, which has more than doubled from 1995 to $27,970 (£18,187), and of the city itself, with construction accounting for 71 per cent of Seoul’s 37,843 tonnes of daily waste in 2012.

Seoul has, however, set its sights higher and is, as of 2013, a ‘Zero Waste City’, with a 2020 target of 70 per cent recycling, along with a 30 per cent reduction in food waste. Landfilling of food waste was banned in 2005, and the Seoul Metropolitan Government wants nothing heading to landfill by 2017. Each district has been tasked with reducing municipal solid waste by 600 tonnes per day by 2016, with those meeting goals exempted from waste treatment fees and those missing the targets picking up the increased bill.

Food waste, which makes up almost 30 per cent of Seoul’s waste, is a particular focus. Hosting etiquette and ordering practices at restaurants mean that food waste is a cultural issue. This is perhaps encapsulated by kimchi – a Korean staple made of fermented cabbage and every seasoning available – that produces plenty of scraps. Hong explains: “In our food culture, if you order a dish then all these different sides accompany it. You never order kimchi in Korea – you order something else and it comes with it.” The government tried to introduce an à la carte system, where side dishes had to be ordered but, as Hong says, it was a total failure: “People have become so accustomed to the way things are that they just couldn’t understand that you have to order kimchi, you have to pay for kimchi.”

This article was taken from Issue 82

This article was taken from Issue 82The VBF system initially helped with food waste, removing it from the residual waste stream, but between 2008 and 2012 the nation’s food waste generation increased by three per cent each year, and food waste disposal is now estimated to cost over £450 million per year. Thus, in 2012, a charge on food waste was also introduced. Now 22 million households, as well as restaurants, food stalls and the fresh food sections of supermarkets must pay for their food waste by weight.

Apartment blocks in Seoul have been fitted with large, high-tech food recycling bins: residents scan key cards to open the bins, which then weigh new additions and automatically charge the fee to the cards. In the first half of 2013, 1,978 tonnes of food waste was generated per day in the 25 districts of Seoul, down 10 per cent from the same period in 2012.

The city has clearly learned a number of lessons that could be applied to other megacities or cultures struggling to keep waste generation down. “For a system to work, you have to understand how people generally behave: your culture, how people respond to a particular policy or programme”, Hong says, referencing Seoul’s short-lived menu initiative. “So I think it’s different from country to country, region to region. If people do not agree with and comply with the system, it can’t work.

“Most of all, however, communication is vital. If people are not on the same page, they will illegally dump it or burn it. You have to persuade people why it is needed, why the system is reasonable and why we should actually do this. It’s for the welfare of our whole people, not just our government. That kind of persuasion is very important."