The future of organics recycling

The organics sector is earmarked for great change in the coming decade, with tonnages of waste sent to anaerobic digestion and composting set to increase dramatically. But problems of contamination and capacity persist and will need to be resolved in the medium term

Organics has long been in the slow lane of recycling in the UK. Local authority food waste collection is still spotty. Only 160 – less than half – of local authorities offer a kerbside collection and household garden waste is largely an optionally paid-for extra with much still ending up in landfill.

But the 2020s is set to be a decade of growth for the sector. The government is planning to make food waste collection mandatory from 2023 and proposes introducing free garden waste collections. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) estimates that food waste collected will increase by 1.35 million tonnes by 2029. The catch is that there are still a number of unresolved issues that need to be overcome if the sector is to reach its full potential.

In the midst of all this are a number of proposed new regulations. The Government is due to report back on a consultation regarding Appropriate Measures Guidance for the biological treatment of waste as well as revisions of the current Quality Protocols and Standard Rules for organic waste treatment.

It is hoped the latter will get to grips with the age-old problem of contamination. The PAS 100 and PAS 110 certifications should (in theory) ensure a basic level of quality for composting and anaerobic digestate respectively, but some industry observers, such as Tony Breton, the UK Market Developer for the Italian bioplastics firm Novamont, suggest their presence hasn’t made that much of a difference: “As it’s currently done, all the responsibility for quality is placed on the processor. Then, depending on where you are in the country and what your Environment Agency officer is like, they will see what comes through the gate as fine or not. The pattern that we’re seeing is that, say, if there’s five per cent contamination coming in – and most of that is plastic – by the time it’s gone through an organics process of carbon loss, the water loss and everything else, the five per cent has gone up to 18 per cent.”

Jenny Grant, Head of Organics at the Renewable Energy Association (REA), says that quality has to be improved at source: “Education and communication is going to be key in getting it right. There is lots of evidence about the link between the levels of quality and the amount of proper communication with householders.”

“But,” she adds, “unfortunately at the moment there is very little spare money for that sort of thing! It’s something we’ve called for from central government in our response to consultations. Without that I don’t think that things are going to change. Many local authorities have zero budget for communications. And then they wonder why householders don’t know what to put in their bins.”

Additionally, it’s unclear what effect the introduction of free garden waste collections (assuming it goes ahead) will have on quality. “When we asked our members about those proposals there was a really mixed response,” explains Grant. “Some said ‘yeah great! We’ll capture more and there’d be less garden waste going into residual’. Others said, ‘no, paid-for works well and making it mandatory means people who don’t want it will just have an extra unwanted bin.’ I think it has the potential to reduce the levels of contamination but it’s really going to depend on how it’s managed by individual authorities. It needs to be shaped on a local level – if you live in a really rural area with lots of gardens then it makes more sense than in, say, a built up urban area.”

Destination unknown

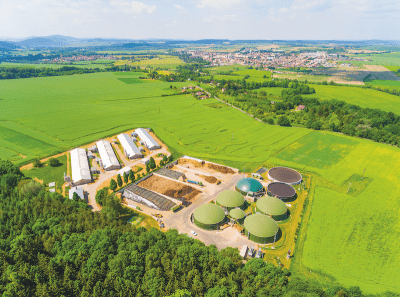

Assuming that the sector can improve its quality issues there is also the question of where all this new organic material will go. At present wet anaerobic digestion is the main destination for Britain’s organic waste and indeed there are now over 570 AD plants in the UK with another 330 under development. Compare that to just 170 UK industrial composting facilities.

There are, however, problems with wet AD. It can emit ammonia into the atmosphere and in the wake of the Appropriate Measures Guidance it looks likely that there will be restrictions on how it is stored. “The industry going forward is going to have massive changes in terms of its cost base,” explains Breton. “Currently, you’re allowed to produce digestate and then stick it in an open lagoon. But it isn’t stable – it just sits there bubbling away, spitting out methane and nitrous oxide! So given that you’re going to see 2-4 million tonnes of food waste coming along you’re going to need to cover and store it.”

There is also the problem of where you can spread it. Around 55 per cent of land in England falls in Nitrate Vulnerable Zones, which limit nitrate pollution in rivers. And there are restrictions on the time of year it can be used – according to Nitrates Directive legislation you can only spread it when there is ‘crop benefit’, which means dry days in spring, often a rarity in the UK.

In contrast there is more flexibility regarding compost use. Breton feels that the two sectors need to work together. “You’d hope that the two would become ‘friends’, shall we say. At the moment it’s seen as if it’s a fight between AD and composting despite all the issues you have with digestate quality.” One solution could be to co-site AD and composting facilities, thus reducing transport costs: “That would be the sensible thing. You can see it happening in the medium term. In the short term everyone is going to be fighting for what they’ve got.”

In contrast there is more flexibility regarding compost use. Breton feels that the two sectors need to work together. “You’d hope that the two would become ‘friends’, shall we say. At the moment it’s seen as if it’s a fight between AD and composting despite all the issues you have with digestate quality.” One solution could be to co-site AD and composting facilities, thus reducing transport costs: “That would be the sensible thing. You can see it happening in the medium term. In the short term everyone is going to be fighting for what they’ve got.”

There is a worry too from some quarters that the current growth in residual waste treatment will end up crowding out investment for organics waste treatment. “I think it depends on what the next stage of the Resources and Waste Strategy consultation comes up with,” says Professor Stephen Jenkinson, who was the CEO of the PFI between Viridor and Greater Manchester Waste Authority. “If they legislate for mandatory food and/or garden waste collection those materials will need to go to organics recycling so they are not really suitable to go to an energy-from-waste plant. If legislation is drafted well I don’t think they will take over from the organics recycling sector. I’d like to think that organics will go to organics recycling, not to any other process that’s further down the waste hierarchy.”

Building markets

In addition to issues surrounding infrastructure capacity there is also the question of end markets for solid organics. The current net value of the products – around £5 per tonne for compost (even less for digestate) – reflects this and indeed contributes to what is, in effect, a vicious circle. “At the moment the value of digestate is not fully appreciated and, therefore, given a sufficient market price,” says Charlotte Morton, Chief Executive of Anaerobic Digestion and Bioresources Association (ADBA). “Until that changes it’s difficult for people to invest in improving the processing to put it into a higher quality. It’s been an issue for years – how do you improve the market price? Because that would be a complete game changer in terms of the economics of it all.”

“There are barriers,” admits Grant. “Especially around fibre digestate products or digestate-derived products. There is market potential there but at the moment there is little incentive for operators to do an awful lot on that. The Quality Protocol as it stands doesn’t permit fibre digestate to be used in that higher value market, like in say horticulture.”

She suggests government legislation may be one option. “There is possible growth in the ‘growing media’ sector, which produces bagged products for gardeners. I think there is potential for most compost and fibre digestate to be used as say, peat replacement. There are economic barriers to this as peat is generally cheap, but if the Government were to legislate that it can no longer be used then would drive up demand for other solid outputs.”

Stephen Jenkinson insists that the key is to engage with farmers. “In many ways the market is farmers. I think they have really lost faith in what we term a ‘soil conditioner’. The farmer prefers something that he understands and usually that’s chemical fertiliser. He knows what it does. Farmers only use it three or four months of the year and yet it (compost and digestate) is coming out every day.”

Jenkinson suggests that the one solution might be to essentially fix the market, by giving farmers a financial incentive every time they use compost instead of chemical fertiliser. The downside, he admits, would be the huge expense involved: “Well, yes. If we want to avoid organics going into landfill there will be a cost to it – more than what we’re spending now. But if you’re talking about getting quality compost that is acceptable to the user we cannot do that with the current technology and current quality controls that exist. The investment for compost is not there because it doesn’t make money.”

What is certain is that a significant amount of research and development needs to go into creating those markets to make the whole sector economically viable.

“I have no passion for WRAP,” says Breton. “But what they did do which was good was their organics programme. They spent millions doing all the research, pathogen research, market development – they did a lot of work with the agriculture sector, the horticultural sector and other wacky uses for compost and digestate. What was hoped for was that the industry would then carry on that work, but it didn’t. Austerity came and that investment was never continued.”

A green future?

Perhaps a way forward for the sector will be clearer when the Government reports back on the Appropriate Measures. Breton isn’t confident that what emerges will deal with the immediate challenges the sector faces. “What’s going to come out of it is probably a lot more cost for the organics side! We need a better understanding within the organics sector – for both composting but also digestion – in terms of contracts. These Appropriate Measures are going to come through and there’s going to be a lot of new costs coming into the sector and you’re going to have a lot of operators in these contracts that they can’t actually change.”

This article was taken from Issue 100

This article was taken from Issue 100“There might be sympathy but there wouldn’t necessarily be enough, say, good faith if it’s going to cost them another £5 a tonne. I know the Environment Agency is looking at developing some sort of five-year plan to address contamination within the organic system. But the problem with it is unless that five-year plan is somehow linked into Appropriate Measures or becomes statutory guidance it’s just a nice fluffy voluntary thing where the onus is completely put back on the operators.”

“The consultation is undeniably a good thing,” says Jenkinson. “However, we still suffer from quality issues, which is the one thing holding everything back. Financially, if there’s no incentive to do something then you won’t do it. If something came along via Additional Measures where financially it’s not affordable you’re not going to do it.”

It’s important to step back from all this and see what’s at stake here. Organics is an area of massive growth potential, but one that needs to be nurtured properly, by all the stakeholders, for very important reasons. “As a sector it’s absolutely critical,” says Morton. “In delivering the level of emissions reduction that we need, providing food security for us and creating jobs – it’s been estimated between 30-60,000 jobs.”

“We should absolutely be prioritising it, especially in the lead up to COP26. It’s an area the UK could really show some leadership in and, in turn, influence the rest of the world.”